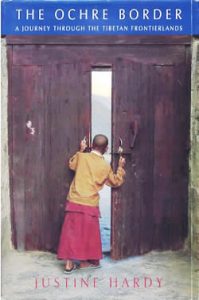

The Ochre Border – A Journey through the Tibetan Frontierlands

First published in hardback in 1995, an account of the author’s journey with three friends to a valley in the Himalayas, unvisited for 70 years. Situated on the Indo-Tiberian border, it is an area which is completely untouched by the modern world.

Read an extract…Read a review… View the photo gallery…

Extract – Part 1

The Ochre Border

A small boy with a shaven head picks himself up out of the dust. His puppy – wrestling companion flicks his robe over his shoulder and walks away, the stubble on his head picked out by the early morning light. The boy shakes like a dog; a cloud of dust comes from his ochre robes. He sets off with a crab-like gait but, as he walks, he straightens and becomes older. He approaches a stranger standing in the corner of the monastery courtyard.

‘Do you read the books of Julian Barnes?’ asked the eight-year-old Buddhist novice.

This is a scene from the Spiti Valley on the Indo-Tibetan Border. If you looked at an atlas it is on the dotted line between the pink of India and the yellow spread of China; part of the border area that does not appear to belong to anyone. It is a last untainted pocket where the past runs up against the future.

India cheered Independence in 1947 and two years later Mao Tse-tung announced The People’s Republic of China. For a pregnant moment the two nations embraced each other; the new juvenile leads that had escaped from the wicked stepmother of ruling oppression. The pantomime ended in 1949 when Peking Radio and the official New China News Agency announced that ‘Tibet as well as Turkestan are integral parts of China,’ and ‘The British and American imperialists and their stooge, the Indian Nehru government,’ ran the risk of ‘cracking their skulls against the male fist of the great Chinese People’s Liberation Army’ if they gave their support to Tibet. The following October the ‘male fist’ massed on the Eastern Border and invaded Tibet.

Extract – Part 2

Introduction – Ochre Continued…

The Tibetans crumpled in the Chinese sweep across their country. The cultural and physical pillage and torture that followed are still an unfolding twentieth century horror story.

But, in the high reaches of the Himalayas, near the Indian Border, satellites of Tibet survived intact. They are known as the disputed border area and waved the Indian flag at the Chinese to shout their impunity. They shut their borders and waited for the danger to recede.

In 1977 small parts of these areas were opened up with a certain amount of big brother watchfulness. Permits were limited. They were often ignored by recalcitrant border police who wielded their permit stamps like AK47s.

In 1992 the Spiti and Lahaul Valleys once more opened their borders to a few visitors. For those who managed to wheedle past the jumpy border guards the reward was to find an area of the The High Himalayas that has managed to preserve itself as a severed limb of Tibet; an anachronism of Tantric Buddhism and medieval farming methods.

The people weave their lives around a labyrinth of demons, saints and holy men. Their religious rituals shroud themselves in the same sort of mystic diversity that spreads from the intensity of the Catholic Communion to the merry extreme of hanky waving Morris Dancers.

Their Buddhism runs parallel with their daily lives. The shrines in their homes are splattered with cooking fat and they will recite a mantra (sacred phrase) in the same breath as they yell at their yaks.

Theirs is a disappearing world that is being chipped at from the outside. As the borders open the travellers will begin to filter in. With each click of the visitors’ camera shutters the mountain people get a bit wiser to the fast buck potential of tourism.

When we walked in they were villagers in high places raised on a diet of barley flour and Buddhism. What does that make them? Neither gods nor strange inbreeds. They are a high altitude people with raisin skin and a wicked sense of humour. They use wooden ploughs pulled by yaks; they hum mantras in the same way that we burble advertising jingles; they feed their dead to the birds; they gallop on tiny ponies across mountain rubble and they believe in primogeniture.

Few people have seen these valleys. More will, but at the risk of losing the bloom off the fruit. To each visitor it will mean something else; an area with a chameleon aspect. Rudyard Kipling described a scene in Kim when the young man and the old lama reached the Chinni Valley. On a map the valleys are many days climb apart but the description could have been Spiti:

‘At last they entered a different world within a world – a valley of leagues where the high hills were fashioned of the mere rubble and refuse from the knees of the mountains . . . surely the gods live here, beaten down by the silence and the appalling sweep of the dispersal of the cloud shadows after rain. This place is no place for man.’

So I decided to go.

Reviews

“Justine Hardy’s insightful account of travelling to the Spiti Valley in the Northern India Himalayas is a frank and entertaining book.It details personal perceptions and preconceptions of a reasonably organised group heading to an area of Himachal Pradesh ,until recently, closed to Western travellers due to its strategic location. Their contact with a formerly isolated culture evokes many surprising and some comical moments as does the inevitable internal politics of group travel in such an arduous environment.”

Reader review on Amazon

Photo Gallery

Click on the thumnails below to view a larger image.